Jumping Worms

Free printed copies of pest alerts are available.

Jumping worms (Amynthas spp.) have spread across the United States after their introduction to the Northeast through imported potting soil, mulch and compost. These invasive annelids threaten woodlands and other natural areas by rapidly destroying soil structure and depleting soil nutrients.

Environmental Concerns

Invasive jumping worms threaten ecosystems, particularly woodlands, by consuming organic matter that causes soil erosion on the top layer (Gupta & Van Riper 2023). The worm’s “coffee ground” casts further degrade the soil’s ability to retain water, air and nutrients. The erosion and loss of structure reduces the soil’s capacity to harbor native plant species and soil organisms.

Origin and Distribution

Invasive jumping worms originated in eastern Asia. The United States recorded its first sighting of the jumping worms in the late 1800s. Jumping worms have spread to 38 U.S. states since introduction, predominantly in the Northeast, Southeast and Midwest.

The earthworms frequently found in lawns across the United States or used for vermicomposting (Eisenia spp. or Lumbricus spp.) are also not native to North America and originated in Europe. While these “nightcrawlers” can damage forests ecosystems, they are not a problem in garden settings. Jumping worms pose problems in both settings.

However, these species do not cause the same ecological disruptions as invasive jumping worms. Visit this distribution map to see where jumping worms have been reported.

Identification

The three most common jumping worm species found in the United States are Amynthas agrestis, Amynthas tokiensis and Metaphire hilgendorfi. These jumping worms share three distinct features that clearly distinguish them from common European earthworms.

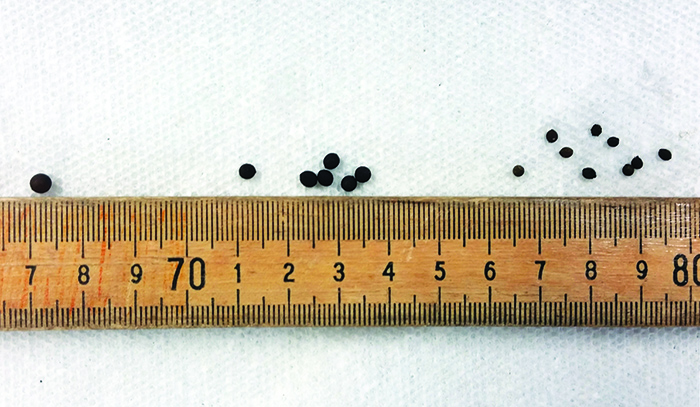

First, jumping worms have longer (7-20 cm), darker and more rigid bodies. Second, the clitellum band located close to the head wraps entirely around the body and has a clear milky white color. Finally, the jumping worm violently and actively moves when poked or disturbed and may lose its tail.

Jumping worms typically live in the top two inches of soil and feed on organic matter in leaf litter and mulch. Signs of jumping worm presence in soils include “coffee ground” casts and diminished soil structure. Plants grown in jumping worm–infested soils often exhibit stunted growth.

Life Cycle

Adult jumping worms die at the end of each growing season, unlike European earthworms that overwinter as adults in the soil. Jumping worm offspring overwinter in cocoons and hatch the following spring. The offspring can reach sexual maturity and shed their cocoons within 60 days, and jumping worms do not need a mate to reproduce.

This short maturation period and ability to reproduce asexually allows the worms to produce two generations per season, leading to rapid population growth (Beglinger 2002).

Management

Preventing Spread of Jumping Worms

Unfortunately, there are limited options to manage jumping worms. Preventing the spread of invasive jumping worms is the best control method. Untreated or uninspected mulch, compost, potted plants or soil may contain jumping worms (WDNR 2023).

Consider purchasing bare root stock plants instead of potted plants. Do not use jumping worms as bait. Fishing companies have sold jumping worms as bait using names such as Alabama jumper, disco worm, snake worm and crazy worm.

Avoid jumping worm introductions into new habitats by cleaning boots, tools and equipment after each use and inspecting imported lawn materials of mulch and compost for jumping worm cocoons and adults.

Cultural Controls

Sourcing mulch and compost locally from licensed manufacturers will best avoid jumping worm introductions (Johnston 2023). Alternative soil amendments of pine needles, hay or native grass mulch may, also, create unfavorable conditions for jumping worms.

Finally, limited data shows that biochar soil amendments reduce European earthworm populations, but this research does not investigate jumping worm control.

Physical and Mechanical Control

Soil solarization can effectively manage jumping worms where confirmed or suspected. Solarization works by sandwiching soil, mulch or compost between two layers of black plastic resulting in temperature increases from sun exposure.

Soil solarization can effectively manage jumping worms where confirmed or suspected. Solarization works by sandwiching soil, mulch or compost between two layers of black plastic resulting in temperature increases from sun exposure.

Jumping worm cocoons will die when exposed to sustained temperatures above 104° F over three days (Johnston and Herrick 2019).

Chemical Control

There are no pesticides registered in the United States for suppression of earthworms or jumping worms. Some conventional pesticides such as Carbaryl and biopesticides such as BotaniGard ES, EPA #802, will kill worms but do not list worms as a target pest on its label (Nouri-Aiin & Gorres 2021). Managers should avoid pesticide applications on pests not listed on the label.

Report Sightings

Ongoing monitoring of populations provides critical information for research. Report any sighting of jumping worms using EDDMaps or the Great Lakes Early Detection Network. Where jumping worms are suspected, they may be monitored by pouring a gallon of water with 1/3 cup ground mustard slowly over the site.

This mix of water and mustard will bring jumping worms to the surface and enable manual removal. Managers can desiccate the collected worms in soapy water and dispose the carcasses in two or more tightly sealed plastic bags.

References

Beglinger, J. (2022). Jumping worm (Amynthas spp.) Cornell Cooperative Extension Genesee County. bit.ly/47nSIxr

Gupta, A., & Van Riper, L. (2023). Jumping worms. University of Minnesota Extension. https://extension.umn.edu/identify-invasive-species/jumping-worms#habitat-1883160

Johnston, M. (2023). Research update: Jumping worms and sleeping cocoons. University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum. https://arboretum.wisc.edu/news/arboretum-news/research-update-jumping-worms-and-sleeping-cocoons/

Johnston, M. R., & Herrick, B. M. (2019). Cocoon heat tolerance of pheretimoid earthworms Amynthas tokioensis and Amynthas agrestis. The American Midland Naturalist 181(2), 299-309. https://doi.org/10.1674/0003-0031-181.2.299

Nouri-Aiin, M., & Gorres, J. H. (2021). Biocontrol of invasive pheremitoid earthworks using Beauveria bassiana. PeerJ Life and Environment, Article 9:e11101. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11101

University of Georgia Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. (2023, October 4). Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. University of Georgia–Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. EDDMapS. https://www.eddmaps.org

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). (2023). Jumping worms Amynthas spp. https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/Invasives/fact/jumpingWorm

Resources for more information:

Wisconsin Horticulture Jumping Worms page

Acknowledgments

This pest alert was authored by the Lawn & Land Working Group.

For information about the Pest Alert program, please contact the North Central IPM Center.

This work is supported by the Crop Protection and Pest Management Program (2022-70006-38001) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

September 2024